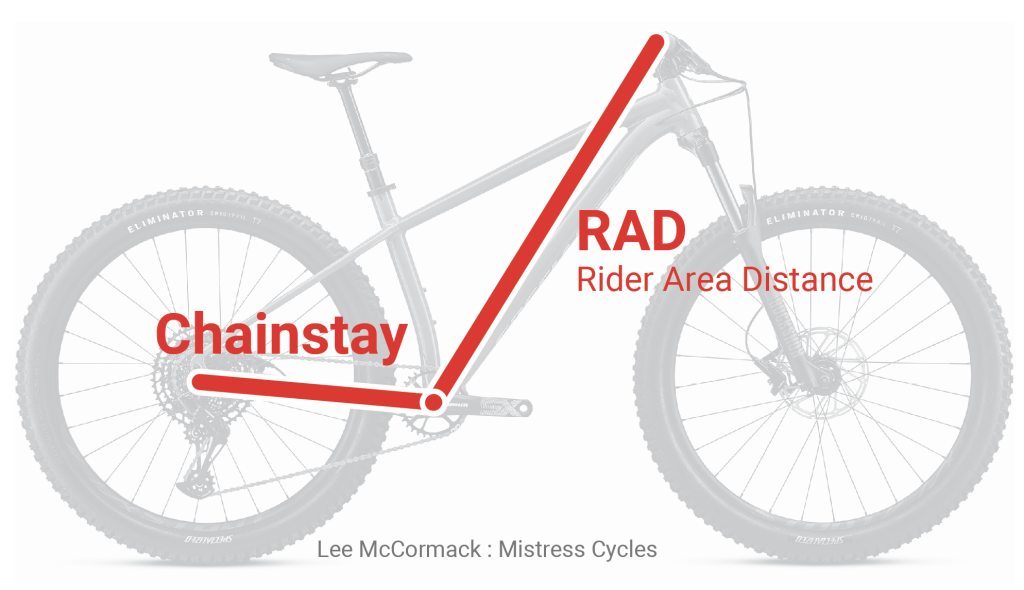

The most noticeably unique feature of Mistress bikes is that, compared with mainstream “patriarchal performance” geometry, the front of the bike is shorter and the rear of the bike is longer. This is obvious in our significantly longer chainstays. Many people ask how this affects the ride.

Let’s get into this, shall we?

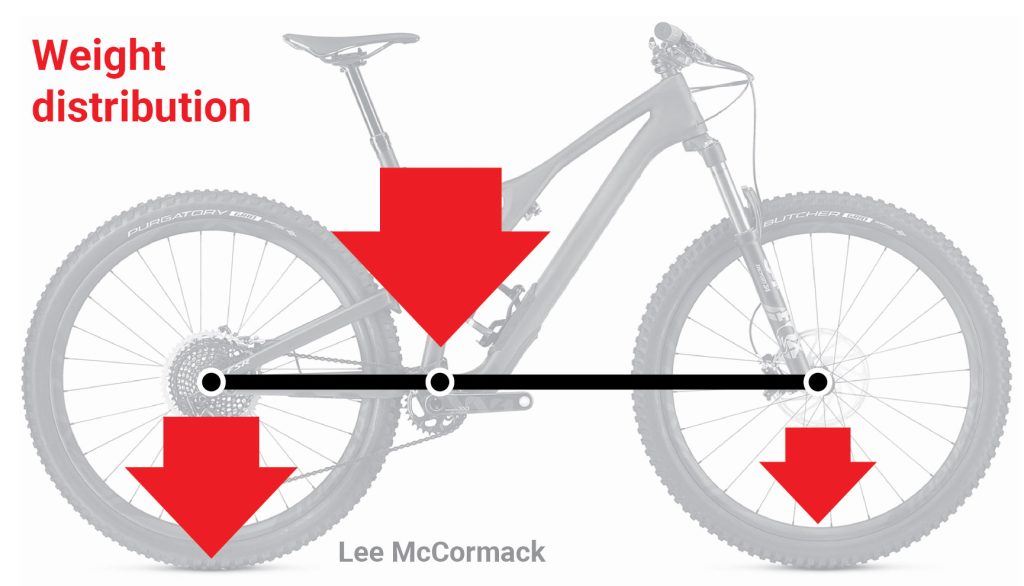

Fore-aft weight distribution

The amount of weight or pressure that drives into each tire is a huge part of vehicle design. The best-handling cars and motorcycles are designed with very specific fore/aft weight balances in mind. According to the Society of Automotive Engineers, the ideal fore-aft weight distribution for a Formula 1 car is 40/60. At a constant speed and direction, 40 percent of the car’s weight is on the front wheels. 60 percent is in back. A driver can change this with brakes and throttle, but that’s the car’s default balance.

Among hybrid bikes and low end mountain bikes, 40/60 weight distribution is common. The original mountain bikes were right around 40/60. I kept noticing that my 2017 Specialized AWOL, a heavy steel touring/adventure bike, cornered better than my fancy mountain bikes. That bike is 40/60. This realization led to the Pink Mistress prototype, which has a 40/60 weight distribution:

Curious about your bike’s fore/aft weight distribution? Divide the chainstay length into the wheelbase. That’s how much weight is on the front wheel when you’re balanced on your feet.

Why are mountain bikes front-light?

For a more detailed description of how modern mountain bike geometry evolved, see Birth of a Brand.

Back in the ’90s we were riding relatively short front ends and long rear ends that put us around that 40/60 sweet spot. Gary Fisher came out with his Genesis Geometry, which claimed that shorter chainstays are better, and that they should be paired with longer front ends.

It started there, and over time that trend got bigger and bigger. I believe Transition was a major driving force. By the time modern enduro bikes emerged from the ooze, manufacturers were in a race to see who could out-longer the front ends while keeping the rear ends short. This is pushing rider’s weights farther and farther back. On a large enduro bike, the front end might have only 33 percent front wheel load and 67 percent rear wheel load.

A 40/60 bike has 20 percent more front wheel traction independent of riding skill. That’s can be difference between washing out and carving, or the difference between corning with caution and cornering with aggression.

The marketing story is basically:

A longer front end (and wheelbase) makes your bike more stable at speed. Never mind that no modern bike is unstable at any speed, or that people have a lot more trouble turning than going straight.

The farther your front wheel is in front of you, the less likely you’ll get flung over the bars. Since this is a core fear, people believe it. If there was no human involved, it makes sense. However, making your bike longer by increasing the distance between the saddle and the handlebar is like making a truck longer by increasing the distance between the front seat and the steering wheel. At some point it’s hard to work the steering wheel, right?

Short chainstays are poppy and playful, which makes them cool. Most of us want to feel cool. If hanging the new whiz-bang enduro sled off your tailgate makes you feel cool, you’re gonna do it. (Ha, what if the short stays are designed to fit ong bikes into Toyota Tacoma crew cab beds?) Fact is, very few riders know how to ride in a style that takes advantage of the higher leverage ratios of short stays. It’s like me buying a short board when I wanted to learn surfing. That’s what the cool bros surfed on, and I wanted to be cool! But I couldn’t catch a single wave until I tried a huge, foam floaty beginner board. In the end, I’d rather ride a board I can catch a wave on than fight a board that looks cool hanging off my tailgate.

The mountain bike industry is so driven by trends that it didn’t take long for all mainstream bike companies to follow this one. Great bikes are panned in reviews if they miss some hot metric. I remember Pinkbike loving a new Stumpjumper then knocking off a star because the reach wasn’t as long as fashion demands. Despite the revieer sayig the Stumpy was the most balanced, capable bike he’d ever ridden.

Big companies with investors and overheads have to sell bikes, so they have to follow the trends. Chris Cocalis from Pivot said the trend toward longer front ends has gone too far, but he has to sell bikes, so he made his bikes longer. He also said the people who work at Pivot, the people who race Pivots and the customers at demos went down a letter size.

I am not throwing shade at mainstream bike companies. They are doing what they have to do in order to stay in business. The bikes work well, but they require a lot of fitness and skill that few riders possess or have the time to develop.

Downsides of front-light bikes

Light front end. Less traction in corners. This makes the front tire wash out. Less traction on seated climbs. This makes the front wheel wander side to side.

Heavy rear end. Because the rear end is extra heavy, it hits bumps harder. This leads to more pinch flats, harsh hits, and getting pitched over the bars.

Bad fit. When the frame reach is too long, the distance from your feet to your hands (RAD or rider area distance) becomes excessive and you don’t have enough arm range to control your bike. You feel like the bike is riding you, you develop chronic pain, and you might get pulled over the bars and experience acute pain.

When it comes to mountain biker hospitalizations, the two leading causes are being flung over the bars and washing out in turns. To sum it up, the industry has made mountain bikes more dangerous to ride in their quest to generate sales. That’s a damning thing to say, but it’s logically sound.

Yeah but what about upsides of front-light bikes?

Let’s be fair here.

Greater leverage ratio between your hands and the rear wheel. This comes from the relatively longer front end and relatively shorter rear end on the bike. If you know how to execute integrated row/anti-row movements when you ride, this allows more explosive pumping, hopping, jumping, cornering and technical climbing. Examples include BMX racing, high level dirt jumping and trials. Learn more.

In my experience working with more than 10,000 riders of all levels, less than 1 percent of mountain bikers ride like this. Lots ot pros and skilled influencers do … and that’s why that imagery is so prevalent. But, statistically speaking, you do not ride in that style.

Why don’t the big companies better balance the riders?

First of all, let me say that companies like Specialized make incredibly refined, sweet bikes. Some really great people work there. Heck, I’ve done testing and freelance work for Specialized, and they sponsored me for 20 years. This is not me bagging on Specialized or other major companies. The realities of business force their hand.

Why don’t they redesign mountain bikes so riders are balanced closer to the middle where they are safer and can actually ride faster and harder?

They can’t risk sales. That’s the biggie. At that level they can’t risk trying something they fear will cost them revenue. A friend of mine works with the owner of a successful chain of bike shops. One of their brands is very high end, very boutique, from a smaller company who took on VC money then released their founder. Sound familiar?

The owner of this shop said to the bike company,

“Look you guys, your bikes are awesome, but I can’t sell them because they’re too long. They just don’t fit people, and I can’t move them. Please shorten the reaches on your bikes, and I’ll sell them like crazy.”

The company replied with, “No. We won’t do that.”

As long as the market demands certain geometry, the industry can’t sell anything else. Paradoxically, the industry and its buddy the media created this situation. It’ll be fun to watch the pendulum swing back to reason.

Operational realities. Let’s say a company decides that a certain fore/aft weight distribution is ideal. Since the reach and front end of each size is different, the chainstays for each size would also have to be different. This costs time and money, plus it requires the companies to track more unique parts. When you add suspension this gets even more complicated.

Most mountain bikes have the same chainstay lengths in all sizes. This makes every size ride differently. The bigger the bike, the lighter the front and and the heavier the rear end gets. For example, here is the amount of front wheel load for a Transition Sentinel at various sizes. The small has 10 percent more load on the front tire than the extra large. The small is a very different (and better handling) bike.

| Transition Sentinel Size | Chainstay | Wheelbase | Front wheel load |

| S | 440 | 1199 | 36.7% |

| M | 440 | 1233 | 35.6% |

| L | 440 | 1263 | 34.8% |

| XL | 440 | 1292 | 34.1% |

| XXL | 440 | 1316 | 33.4% |

| Ibis Ripmo 29 Size | Chainstay | Wheelbase | Front wheel load |

| S | 435 | 1195 | 36.4% |

| M | 435 | 1219 | 35.7% |

| XM (extra medium) | 436 | 1249 | 34.9% |

| L | 438 | 1286 | 34.1% |

| XL | 440 | 1329 | 33.1% |

40/60 Warm Embrace geometry

One of the key features of Mistress Warm Embrace Geometry is 40/60 fore/aft weight distribution, like a Formula 1 car. The NoWukkas hardtail carries so much speed so easily that I cruised it to a PR on our local black DH flow trail.

Each frame’s chainstay length is proportional to the front center such that 40 percent of rider weight is on the front wheel and 60 percent is on the back wheel. Right now every Mistress has custom geometry. Your chainstays will be exactly the length that gives you the ride you want. NOTE: If you want to vary from 40/60 we can certainly do that.

The front wheel gets more traction. The other day I modeled a custom frame for a 6’4″ rider. Compared with the XXL Ibis he’s riding now, his Mistress’ front wheel will have 20 percent more traction. That’s a huge source of confidence. The parts of your brain that currently manage the front tire can rest and have fun (or charge harder).

The rear wheel has less weight on it. This means fewer pinch flats, the rear wheel not hitting things so hard, and reduced chances of getting bucked over the bars.

Mistress Cycles has no investors, overhead or sales targets. I just want to make perfectly fitting bikes that help people get the most from their riding.

Please ask questions in the comments below.

Namastoke,

Lee

For some reason, the bike industry has let this go.